Story by Benjamin Baker /Illustration by Xavier Cabrera Vargas

Story by Benjamin Baker /Illustration by Xavier Cabrera Vargas

Lucy Byard is one of the most pivotal figures in the history of the Seventh-day Adventist Church. Yet many have never heard of her, or have just heard her name in passing as the casualty of a tragic event somewhere in the safely distant past.The details surrounding her death have become so muddled and murky that even otherwise trustworthy historians have repeated major inaccuracies about it.

Byard and the narrative surrounding her last days have been cloaked in mystery and misinformation for much too long. Here is what really happened.

The Person Who Forever Changed Adventism

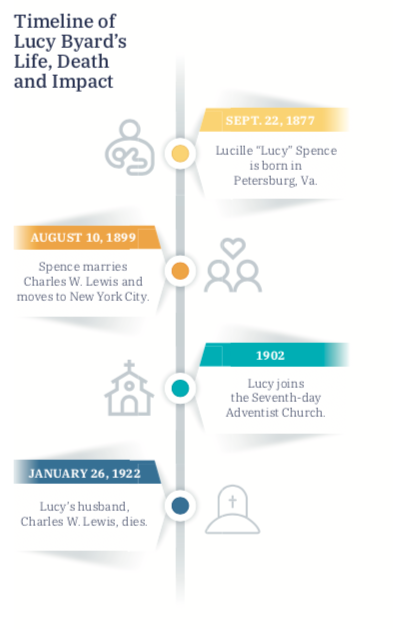

Lucille “Lucy” Spence was born September 22, 1877, in Petersburg, Va., one of eight children of Harriet and Jesse Spence. Born into slavery in southern Virginia in the 1850s, the Spences were emancipated with millions of other African-Americans during and at the close of the Civil War.

As is the case with many blacks in the South during the succeeding Jim Crow era, not much is known about Lucy’s childhood. She grew up in Petersburg and completed her second year of high school, but did not receive any further formal education. On August 10, 1899, Reverend F. J. Walker officiated her marriage to Charles W. Lewis in Allegheny, Pa. Also a Virginia native, born four years after Lucy, Charles became a railway porter. The newlyweds relocated to New York City shortly after their nuptials.1

It was in the bustling metropolis where Lucy discovered the Seventh-day Adventist Church, becoming a member at age 25 in 1902. When she was baptized, she became one of the few black Adventists in the city, a woman with three minority strikes against her: race, gender and religion. Friend and fellow Adventist, Greta Martin, described Lucy as “an earnest, sincere believer and a faithful worker in the cause of the Lord. She always trusted the Lord, never complained, and supported the work of the Master.”2

Lucy’s step-granddaughter, Naomi R. Allen, would later write that Lucy “was a strong, energetic church worker. She was one of five black women who pioneered the work in New York City. All her life she worked untiringly to build up the church.”3

Lucy’s step-granddaughter, Naomi R. Allen, would later write that Lucy “was a strong, energetic church worker. She was one of five black women who pioneered the work in New York City. All her life she worked untiringly to build up the church.”3

Lucy supplemented her lay church work with teaching piano, while Charles chauffeured for a wealthy family. In 1910 the couple lived on 98th Street; by 1920 they rented a house on West 141st Street in Harlem. Tragically, Charles died January 26, 1922, shortly after turning 40, leaving Lucy a widow in the big city.4

Five-and-a-half years later, Lucy found love again. Also from Virginia, James Henry Byard, a 58-year-old twice-widower with five children, who made a living as a cellar worker in Queens. Both were avid musicians, Lucy playing the piano and organ, and James the harmonica. They were married September 23, 1928, at the First Harlem church by James K. Humphrey, a charismatic Adventist minister who would break from the church just one-and-a-half years later.5 In the harshest of ironies, Humphrey presided over the wedding of a woman whose death would bring about the precise change in the church for which he defected.

Lucy was a vital part of church life, playing the organ, teaching piano lessons and directing the choir at the First Jamaica church in Jamaica, Long Island (now the Linden Boulevard church in Laurelton, N.Y.).

Lucy was also a renowned and superb cook, known for her “freshly baked rolls, breads, pies, cakes, nut loaves and gluten,” said Allen.

Throughout the decades, she entertained guests—great builders of the Adventist Church such as J. K. Humphrey, F. L. Peterson, L. B. Reynolds and W. W. Fordham—in her homes in Queens and Long Island. It was said she had a special gift for hospitality. Her home and her heart were open to everyone.6

The Event Who Forever Changed Adventism

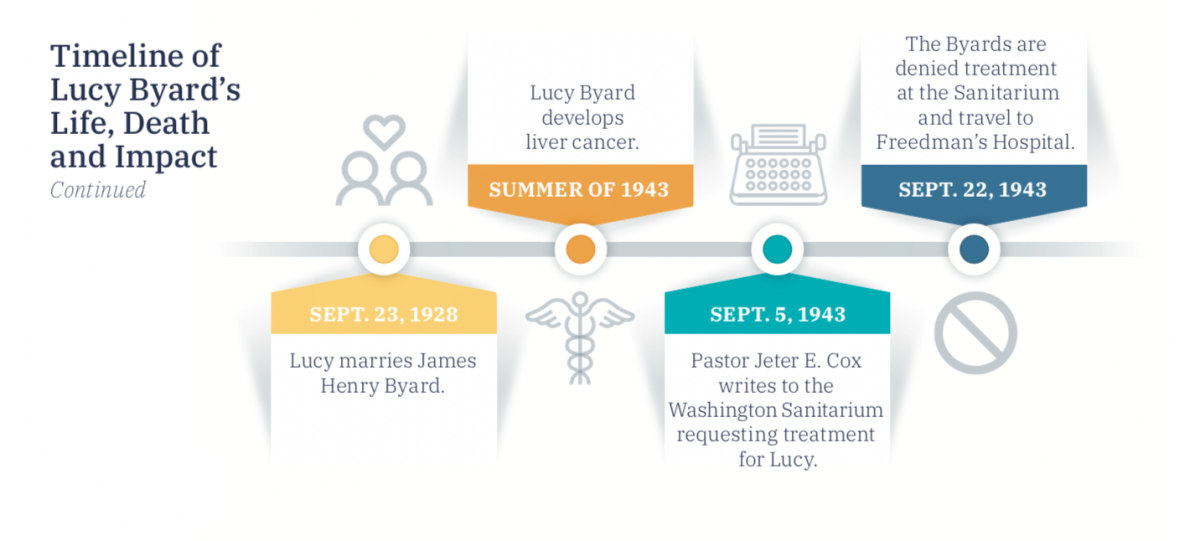

In the summer of 1943, Lucy, by then in her mid-sixties, developed liver cancer with a chronic case of cachexia, or the “wasting syndrome.” According to her husband, James, she “needed careful watch and attendance.” When considering what hospital to take her to, he states that he “was suddenly deeply impressed to send her to Washington Sanitarium in Takoma Park, Md., of which place, I was not referred to by anyone.”7 James asked Jeter E. Cox, an African-American pastor of the Bethel church in nearby Brooklyn, to write a letter of introduction for him to the Washington Sanitarium, arranging for Lucy to be admitted there. Cox was a respected Adventist minister who had pastored in several states and had been the Colored Department representative in the Columbia Union Conference, where the Sanitarium was located.

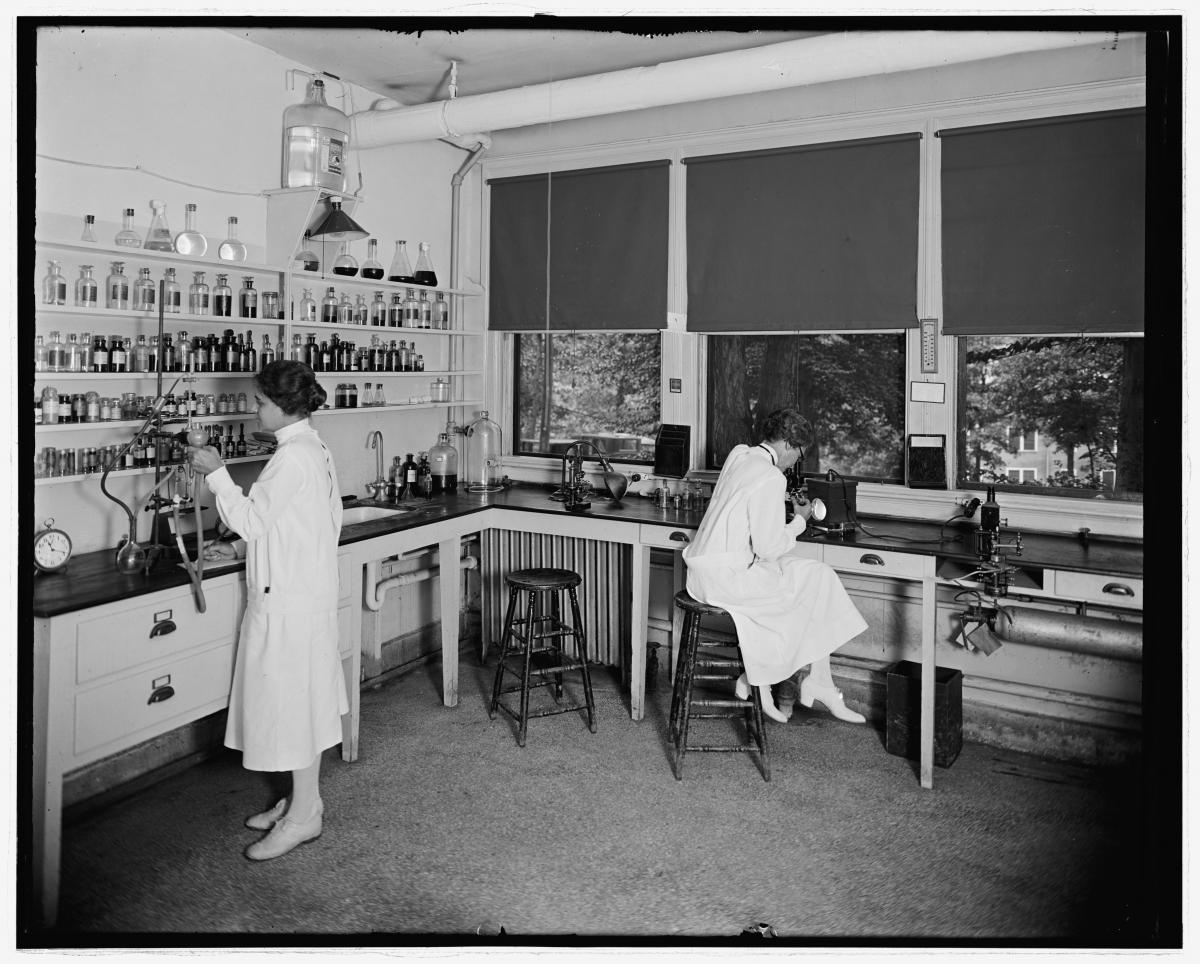

In 1943 the Washington Sanitarium (pictured left in a Libary of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-FB2-2801 image) was a 188-bed facility located just outside of the nation’s capital. Although by the early 1940s, the Sanitarium was moving more toward the hospital model instead of the traditional Battle Creek-esque lifestyle and retreat center, it still adopted a more holistic approach to health and wellness, with a central social component. A 10-member board of directors administered the hospital, including General Conference (GC) officers. Robert A. Hare, a New Zealander from the legendary Hare family, served as medical director since 1938.

In 1943 the Washington Sanitarium (pictured left in a Libary of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-FB2-2801 image) was a 188-bed facility located just outside of the nation’s capital. Although by the early 1940s, the Sanitarium was moving more toward the hospital model instead of the traditional Battle Creek-esque lifestyle and retreat center, it still adopted a more holistic approach to health and wellness, with a central social component. A 10-member board of directors administered the hospital, including General Conference (GC) officers. Robert A. Hare, a New Zealander from the legendary Hare family, served as medical director since 1938.

The practice of admitting and treating black people at Washington Sanitarium and at other Adventist and community institutions was complicated. Prior to 1943, blacks had been treated at the Sanitarium, but on a limited, selective and subpar basis—meaning that only a certain kind of black person would be admitted in emergency cases and the patient had to be treated “in an inconspicuous way” in the basement of the Sanitarium by off-duty hospital staff. By 1943 the policy had changed: no blacks were to be admitted to the Washington Sanitarium.8 It is important to note that when Cox agreed to contact the Sanitarium on behalf of Lucy, he did not know about the reversal of policy. When he had worked in the Columbia Union, blacks could still be admitted to the Sanitarium on a limited basis.

True to his word, Cox wrote a letter to the Washington Sanitarium, dated September 5, 1943, requesting a reservation be made on behalf of James and Lucy Byard and inquiring about assistance with the hospital expenses. Miss Brooke from the Sanitarium’s credit office answered the letter on September 9, with an enclosed form for “part-pay, part-charity care.” Cox responded to Brooke on September 14, advising her that the Bethel church would cover Lucy’s medical expenses, paying $60 up front for the first week, with ensuing hospital bills to be sent to the church. Brooke replied on September 17 that the arrangement was acceptable and that the Sanitarium would be ready to admit Lucy as of Tuesday, September 21.

Due to the gasoline shortage brought on by World War II, the Byards boarded a train and arrived in Washington, D.C., at 7:05 a.m. on Wednesday.

In a letter penned six days later, James described to G. E. Peters, secretary of the North American Colored Department, what transpired:

“We, after much effort, arrived in Washington by rail and went directly to the [Washington Adventist] Sanitarium. I went to the office and informed them that I was Mr. James Byard, of Jamaica, Long Island, and that Elder Cox had made reservations for my sick wife. The attendant acknowledged my reservation, went out and spoke to my wife and proceeded upstairs. He returned shortly and called me into the office, and told me that he regretted to say this, but it was against the law of the State of Maryland to admit colored people into the Sanitarium.

“I, of course, was stunned, for my wife had been looking forward with much anticipation to going to this particular Sanitarium, because she felt that she would be among her own people. There would be an understanding among them that she could not expect in an outside hospital. In fact her hopes were so high that her health was much better than it had been for days, and she even suffered the tiresome and painful train ride because of the expected destination. I warned the attendant of my wife’s condition, and reminded him that she needed immediate attention; also that I was not acquainted with any hospital in Washington, D.C., hoping that he might examine her and find out her critical state, but to no avail. I was utterly confused and tried to get in touch with you, but was unsuccessful. The attendant recommended me to Freedman’s Hospital [now Howard University Hospital], and assured me that she would be accepted there. He called a taxi, told the driver the hospital to take us to, and my wife and I were driven away.”

In closing, James stated:

“My wife is now in Freedman’s Hospital (pictured left) under competent and watchful care. I have now [no] remorses [sic], but I thought I might bring to your attention the sudden and unpredictable manner in which she got there. I would greatly appreciate it if you would, at your convenience, find time to visit her.”9

“My wife is now in Freedman’s Hospital (pictured left) under competent and watchful care. I have now [no] remorses [sic], but I thought I might bring to your attention the sudden and unpredictable manner in which she got there. I would greatly appreciate it if you would, at your convenience, find time to visit her.”9

Medical Director Robert Hare had a different take on what happened, even though he never had any personal contact with the Byards. In a letter to the GC president and secretary on November 15, a full 54 days after the event, and about two weeks after Lucy’s death, Hare is seen in crisis mode, trying to diffuse a tense situation that had spun out of his control. Here is his account of the episode:

“On September 21, a telegram was received at 11:00 p.m., stating that Mrs. Byard would arrive on the 7:05 train Wednesday morning—Elder Cox asking that she be met. As we do not have special means of meeting patients they took a taxicab and arrived at the Sanitarium between 9:00 and 10:00. Mr. [P.L.] Baker called me immediately and told me of the fact that Mrs. Byard was a colored person. In view of the fact that we had carried on our correspondence, not knowing that she was colored, I advised that we receive her into the institution giving her a private room and arrange for her meals to be sent on trays, and plan for her examination and diagnosis by our physicians in off hours, hoping that Mrs. Byard would see the fairness of this in view of our misunderstanding and the social sentiment that exists in Maryland. As an alternative Mr. Baker and I suggested the idea that she might go to Freedman’s Hospital in Washington and have the diagnostic work done which she desired. I did not come to the office to meet Mrs. Byard at the time, feeling that in all probability she would elect to take the private room. When I finished my rounds I came back to my office and inquired what she had decided to do. I learned then that she and her husband had refused to accept our offer of a private room and have gone to Freedman’s Hospital.”10

Hare’s recounting may seem innocuous enough, but half-a-year later, a letter to W. E. Nelson, the GC treasurer and chair of the Washington Sanitarium Board at the time, revealed his true sentiments:

“I cannot feel that the Sanitarium should be called upon to carry a mixed clientele. We have persons of high degree and low degree of the white race and no question exists with regard to their presence here, but were colored patients seen in our buildings there will immediately rise numerous complicating questions and certain groups of our patients such as those coming from Virginia and the Carolinas would be expected to take a degree of offense at their pres- ence. I would just as willingly minister to the needs of a colored patient as anyone else, but mentally, emotionally, and in certain physiological respects they differ from the white, and I do not favor mixing them.”

Hare continued writing that he did “not see any just grounds on which we could say we would maintain a negro ward and limit admissions on a religious basis. This would be quite contrary to hospital practice. ... So we would possibly open a contact with the negro population entering our grounds more or less regularly.

And right now I feel that the Sligo creek and the woods along it are little enough barrier between us and the local negro settlements.”11

Nelson responded:

“You mention that patients from the Carolinas and Virtinia [sic] would object, but I believe patients coming from the District of Columbia and Maryland and from every other State would object almost as strenuously. The psychology of these black people is so different from the white that it would be impossible for us to mix them. Some have suggested that we have a wing in the hospital. That would be all right if we did not have a sanitarium in connection with it. ... As I view the whole situation, Dr. Hare, it is not a matter of the colored people wanting a little sanitarium of their own where they can receive attention, but what they want is racial and social equality.”12

As both accounts attest, the Byards took a taxi across town for approximately six miles to Freedman’s Hospital in Washington, D.C. Founded in 1862 during the Civil War, five years before its current namesake, Howard University, Freedman’s Hospital was the first hospital in the nation of its size and stature, established specifically for the treatment of black people. At the time that Lucy was admitted to Freedman’s, Charles Drew, the renowned medical researcher, was chief surgeon there. James spoke well of the hospital, assuring Peters that Lucy was “under competent and watchful care.”

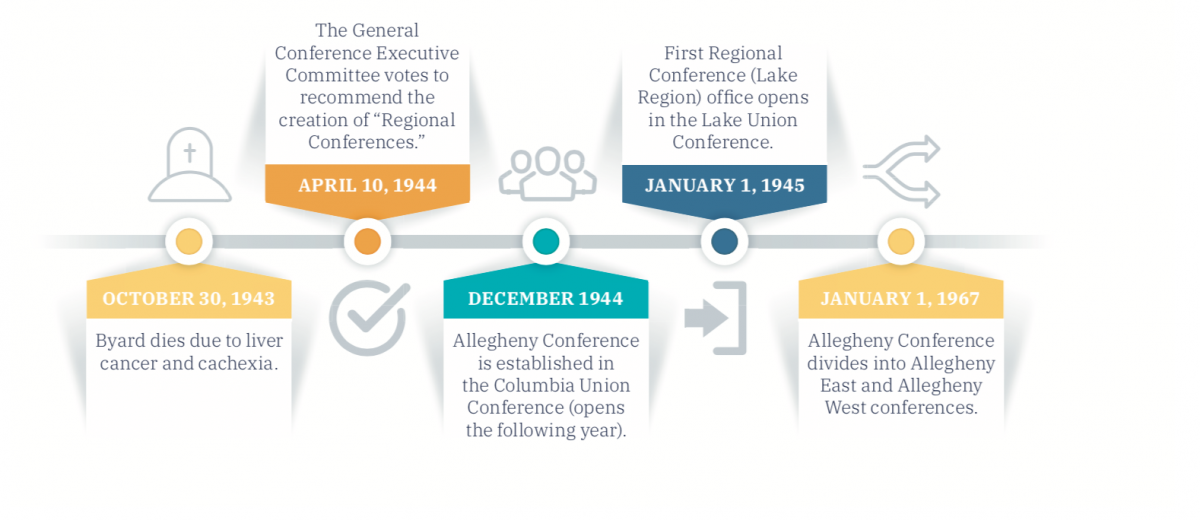

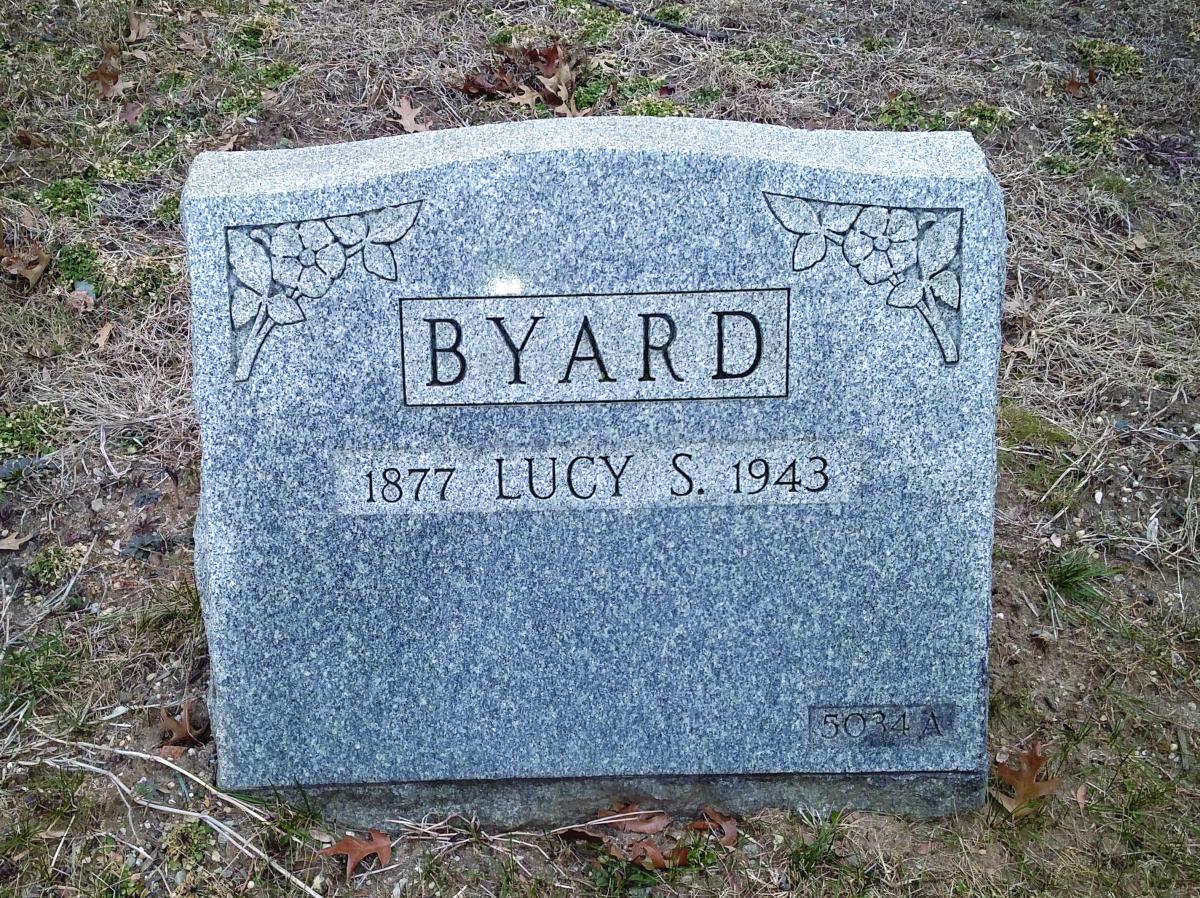

However, Lucy’s condition began to worsen. Thirty-eight days after being denied equal treatment at the Sanitarium, she died at Freedman’s Hospital, October 30, 1943. The immediate cause of death, as listed on her death certificate,13 was liver cancer with a resulting cachexia—literally wasting away. Her body was transported to New York, where her funeral was held at the Ephesus church in Harlem. It is said that hundreds attended and 13 ministers officiated. She is buried at the Siloam section of The Evergreens Cemetery in Brooklyn, N.Y.

However, Lucy’s condition began to worsen. Thirty-eight days after being denied equal treatment at the Sanitarium, she died at Freedman’s Hospital, October 30, 1943. The immediate cause of death, as listed on her death certificate,13 was liver cancer with a resulting cachexia—literally wasting away. Her body was transported to New York, where her funeral was held at the Ephesus church in Harlem. It is said that hundreds attended and 13 ministers officiated. She is buried at the Siloam section of The Evergreens Cemetery in Brooklyn, N.Y.

1 Pennsylvania, County Marriages, 1885-1950, Charles W. Lewis and Lucy Spence, 1899. 2 Greta Martin, “BYARD,” Atlantic Union Gleaner, December 17, 1943, 6

3 Naomi R. Allen, “Memories of My Grandmother, Lucille Byrd (sic),” North American Informant, August 1987, 5.

4 1910 US Federal Census, Manhattan Ward 12, New York, New York; 1920 US Federal Census, Manhattan Assembly District 21, New York, New York.

5 New York Marriage Certificate, No: 22482, September 23, 1928,

6 Allen, 5.

7 James H. Byard to G.E. Peters, September 28, 1943, pp. 1. General Conference Archives, Box: 10991, Folder: “Colored Situation.”

8 See Minutes of the Washington Sanitarium Board Meeting, “Colored Out-Patient Business,” August 29, 1935, General Conference Archives, Box: “Washington Sanitarium Board Minutes 1913 to 1956,” Book: “Washington Sanitarium January 1, 1932 to Jan 1949;” “Explain Why Negro Patients Not Admitted,” January 6, 1937, General Conference Archives, Box: “Washington Sanitarium Board Minutes 1913 to 1956,” Book: “Washington Sanitarium January 1, 1932 to Jan 1949.

9 James H. Byard to G.E. Peters, September 28, 1943, pp. 1. General Conference Archives, General Conference Archives, Box: 10991, Folder: “Colored Situation.”

10 Robert A. Hare to J.L. McElheny (sic) and W.E. Nelson, et al., November 15, 1943, pp. 1. General Conference Archives, General Conference Archives, Box: 10991, Folder: “Colored Situation.”

11 Robert A. Hare to W.E. Nelson, April 6, 1944, pp. 1. General Conference Archives, General Conference Archives, Box: 10991, Folder: “Colored Situation.”

12 W.E. Nelson to R.A. Hare, April 9, 1944, pp. 1. General Conference Archives, General Conference Archives, Box: 10991, Folder: “Colored Situation.”

13 Lucy Byard, Certificate of Death, Vital Records Division, Department of Health, District of Columbia.